Hi all! Fabian here from the think team.

Today I’d like to finally introduce my favorite subject to the table – Neuroscience!

This week some of my friends Amanda and Maya have been talking about the company working culture in their blogs. I’d like to add to that discussion! Here in su-re.co, we are always encouraged to have focused tasks within a day and avoid multitasking as much as possible. Few months ago, we played an activity to illustrate why we should not multitask, and what we should do instead. You can play this game right here right now!

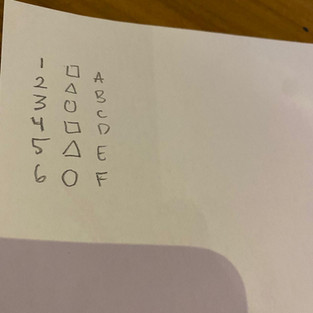

Take a pen and paper and write 1 to 20 vertically. Afterwards, next to it, draw a square, triangle, and a circle in that order, vertically. It should stand next to the numbers. Finally, write ABCs vertically next to it, so it should be A to T. Now you should have three columns with one column filled with numbers, one with shapes, and one with letters.

(yes the list should go on to 20, I just needed to illustrate)

Now in a different sheet or an empty part of the sheet, write what you have written row-by-row. For example, starting from the top you should have “1 (square) A” and then continue to write below that “2 (triangle) B” and so on. Before you do this start a timer and see how you did.

How did that feel? Painstakingly tedious? Yep, but that’s not the only lesson from this activity.

Reset the timer and now write what you have written column-by-column. Start by going 1 – 20, then the shapes, then A to Z. Time it and see how you did. Faster? Much faster? Thought so.

So why is that? Some of you may say it’s cheating, but that’s just how our brains function. If that’s a cheat, then you’d be very interested in Neuroscience. Neuroscience simply provide brain hacks! But why does the brain function that way?

If you’ve ever studied Psychology or Neuroscience, you know that multitasking doesn’t really exist (unless the tasks occupy different cognitive loads, but we’ll ignore that right now). You are simply task switching. If you want to know how well you are at switching tasks, compare the timer results again from the first and second attempt. Our brain was simply wired to focus on one task than multiple ones at once.

Over the years, functional neuroimaging studies (those big expensive machines that look like you’re about to be sent to space) have discovered important brain networks that are involved in multitasking. They are called “executive control” (or sometimes cognitive control) and “sustained attention” which include frontoparietal control network, dorsal attention network, and ventral attention network.

Studies show that task switching shows more activity in the frontoparietal dorsal attention network (Braver et al., 2003). Okay bear with me, this simply means that there is more cognitive demand in switching. Buzzwords aside, the point of these networks is to help in decision making, task building, and goal orienting.

The executive control helps select relevant information once a goal is set, and ignoring irrelevant information. Thus, when you are multitasking, your brain simply cannot choose which information to process, be it from the external environment or internal thoughts. Multitasking in a way is asking your brain to have an internal argument with itself. Not only does this make processing slower, but may actually cause acute stress which hinders performance and memory (Lahnakoski et al., 2017; Uncapher et al., 2016). Who would’ve thought that multitasking could be so damaging.

Moreover, ever feel like you can’t focus on single task? How often do you use social media? Let’s face it, everyone here uses social media a bit more often than we’d like to admit. Social media applications in itself is already quite an overload of information, presenting you with random facts you absolutely don’t need to know. What’s worse is the phenomenon of media multitasking. Ever have your laptop open, say with a video playing, while you scroll through your phone. Or open work on your laptop with your TV on in the background. Well you sir/madam are about to experience the lovely effects of media multitasking by no longer being able to focus....

Remember what I said before, our brains lack the architecture to perform two or more tasks because we need to select relevant information. The moment you get used to multitasking, the brain no longer understands which stimuli is most important to register. Thus, if you’re used to multitasking you will have trouble focusing on doing one thing, because your brain is trained to register anything and process everything. Multiple studies have reported students who media multitasks have trouble sitting through lectures or perform worse in general (Adler & Benbunan-Fich, 2013; Bowman et al., 2010; Harmony, 2013). Moreover, you can feel a sense of inadequacy from the minimal progress, stress hits and more areas of the brain are affected (Lahnakoski et al., 2017).

Well I hope I didn’t end on a negative note, it’s not that your brain is now destroyed (kind of). The beauty of the brain is you get to decide what it can do. After all the brain is the only organ that named itself! The brain is a muscle and so you can train it. Neurons that fire together wire together. Build the habit of prioritizing and focusing on one tasks. This way you’ll be as efficient as possible.

Thanks for reading my blog! Hopefully you begin to understand the importance of Neuroscience in daily tasks. All it takes is a bunch of brain scanners to uncover our capability. I also hope you weren’t doing other things while reading this… I must admit, I was multitasking a lot this week and that’s why I finish my blogs pretty late.

Next week I’ll try to elaborate a bit more on how we can use Neuroscience to combat climate change!

See you next week!

Further reading:

Adler, R. F., & Benbunan-Fich, R. (2013). Self-interruptions in discretionary multitasking. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1441–1449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.01.040

Bowman, L. L., Levine, L. E., Waite, B. M., & Gendron, M. (2010). Can students really multitask? An experimental study of instant messaging while reading. Computers and Education, 54(4), 927–931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.09.024

Braver, T. S., Reynolds, J. R., & Donaldson, D. I. (2003). Neural mechanisms of transient and sustained cognitive control during task switching. Neuron, 39(4), 713–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00466-5

Harmony, T. (2013). The functional significance of delta oscillations in cognitive processing. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 7, 83. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2013.00083

Lahnakoski, J. M., Jääskeläinen, I. P., Sams, M., & Nummenmaa, L. (2017). Neural mechanisms for integrating consecutive and interleaved natural events. Human Brain Mapping, 38(7), 3360–3376. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.23591

Uncapher, M. R., K. Thieu, M., & Wagner, A. D. (2016). Media multitasking and memory: Differences in working memory and long-term memory. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 23(2), 483–490. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-015-0907-3

Comments